The Single Electricity Market and the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland

Lisa Claire Whitten, Niall Robb, and David Phinnemore

May 2023[1]

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

Introduction

One of the less discussed aspects of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland is the provision it makes for the continued operation of the Single Electricity Market (SEM) on the island of Ireland, and so the supply of electricity to Northern Ireland after Brexit. This is achieved through the continued application of certain EU acts in Northern Ireland.

As with the Protocol’s provisions for the free movement of goods across the land border, the arrangements for the continued operation of the SEM will continue to apply provided the Protocol secures the ‘democratic consent’ of members of the Northern Ireland Assembly (MLAs) when they vote in 2024 and potentially every four years thereafter. If ‘democratic consent’ is not forthcoming the Protocol’s SEM provisions will cease to apply after two years. In the meantime, the UK and the EU will endeavour to reach agreement on how to proceed.

This explainer introduces the SEM, explains why the Protocol contains provisions regarding the SEM, notes the EU acts that continue to apply in Northern Ireland, assesses their significance, and considers some of the challenges and complexities related to their application.

What is the SEM?

On the island of Ireland, the electricity industry operates in one wholesale market known as the Single Electricity Market or ‘SEM’. This means that any electricity used in either Northern Ireland or Ireland has been bought and sold through a central market where electricity power generators sell to electricity suppliers who in turn sell to consumers.

To enable the SEM to work, the two electricity grids in Ireland and in Northern Ireland are physically connected. By implication, any wholesale electricity that is generated anywhere on the island of Ireland enters a single electricity market – the SEM – regardless of whether the generator is located north or south of the land border.

Operation of the SEM is facilitated by the Single Electricity Market Operator (or SEMO) which is a contractual joint venture between the two system operators on the island of Ireland – SONI (System Operator for Northern Ireland) Ltd in Northern Ireland and EirGrid Plc in Ireland – and enables the technical and financial coordination that underpins the SEM. SEMO therefore effectively ‘owns’ the rulebook when it comes to the generation and sale of electricity across the island of Ireland. For instance, SEMO sets the technical rules that govern the minimum threshold for a generator’s participation in the market and the procedures for the market’s operation, such as the timing of the regular auctions of electricity that take place.

The SEM is jointly regulated by the Single Electricity Market Committee, made up of three representatives from Ireland and three from Northern Ireland along with two independent members. Its purpose is to protect the interests of consumers of electricity on the island of Ireland by promoting effective competition between generators and traders.

When was the SEM established and why?

The SEM was established in UK law under legislation – the Electricity (Single Wholesale Market) (Northern Ireland) Order – that passed in March 2007 and the market ‘went live’ in November of that year. It operates with dual currencies (€/£) and, when it opened, it was the first cross-jurisdictional wholesale electricity market of its kind in the world.

Cooperation in respect to electricity supply on the island of Ireland first began in the 1970s. This was, however, interrupted due to security concerns during the ‘The Troubles’ but reinstated in 1995 following paramilitary ceasefire agreements. At this time, the UK and Irish Governments believed that the integration of electricity infrastructure on the island of Ireland would increase efficiency and reduce prices; the creation of the SEM in the early 2000s was underpinned by this motivation as well as a desire to extend competition through the liberalisation of the sector and to facilitate decarbonisation.[2]

The SEM was duly created in 2007 by amending existing Northern Ireland legislation on the wholesale provision of electricity in Northern Ireland. Parallel provisions were introduced in Ireland.[3] The effect of the amended legislation was to oblige all but the very smallest power generators to ‘bid in’ their power to the collective market for suppliers to buy and sell on to consumers. What this means is that electricity generation on the island of Ireland is available at the lowest cost source possible to meet customer demand at any given time. On average, each year the SEM manages financial flows of approximately €3.5 billion.

In 2018, the SEM underwent significant change as part of an EU-wide initiative to create a fully liberalised internal electricity market. The main aim of the new ‘Integrated Single Electricity Market’ or I-SEM was to maximise competition and therefore enable access to cheaper sources of electricity by linking trading on the island of Ireland with trading in the wider EU market using European market procedures. The development of the I-SEM took place in the context of the 2009 Electricity Regulation as well as emerging issues in the market design as a result of the increase in renewable sources of electricity being generated. The 2014 SEM Committee decision on the I-SEM stated that ‘Efficient implementation of the EU Target Model is the main driver for the introduction of I-SEM.’

Delays to the development of the I-SEM led to a specific opt-out for Ireland and Northern Ireland being written in to the EU’s network code on Capacity Allocation and Congestion Management, the underpinning legislation for the EU-wide Single Day Ahead Coupling (SDAC) mechanism. The I-SEM went live in October 2018 connecting the SEM to the EU-wide electricity-trading arrangement, SDAC, via Great Britain.

The SEM is connected to Great Britain via two interconnectors which allow the SEM to import electricity when supply is short or to export when supply is high (particularly when there is excess wind generation). Following Brexit and the consequential UK(GB) withdrawal from the EU’s Internal Energy Market (IEM), the inefficiencies in trade across interconnectors and the resultant higher prices, may have had a knock-on effect on prices in the SEM. The SEM Committee has consulted industry on any improvements which could be made to the current arrangements for trading electricity between GB and the SEM.

The SEM and the Prospect of UK Withdrawal

When in August 2016, the First Minister and deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, Arlene Foster and Martin McGuinness wrote to Theresa May, the UK Prime Minister, to provide their initial assessment of significant issues for the negotiation of the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union, the third item on their list was the question of energy supply into Northern Ireland. That energy was a ‘key priority’ followed from ‘the inherent cost and supply issues’ of Northern Ireland being ‘a small and isolated market’. Foster and McGuinness insisted that ‘we will need to ensure that nothing in the negotiation process undermines this vital aspect of our economy’. May responded recognizing ‘the unique issues raised by the single electricity market’ and committed to resolving the them as ‘a priority for the Government’. The commitment was reflected in a position paper in August 2017 where the UK Government noted cross-party support in Northern Ireland and Ireland to maintain the SEM and stressed ‘the need to continue the operation of a single electricity market’ (emphasis added). It was keen to see the structures of the SEM remain and proposed that the withdrawal negotiations ‘cover how best to avoid market distortions within a single electricity market… and ensure that future legal and operational frameworks do not undermine the effective operation of an integrated market’. The aim of the UK government by October 2017 was ‘if possible’ to have ‘agreed specifically on key principles for the energy market in Northern Ireland and Ireland’ as an outcome of UK-EU negotiations. It was not indicated how market distortions within a single electricity market could or should be avoided. The Joint Report from UK and EU negotiators on the state of negotiations on the terms of withdrawal agreed in November 2017 made no reference to the SEM, although it could be inferred from the ‘backstop’ position for allowing the continued free movement of goods across the Irish border that regulatory alignment with relevant EU acts was the most obvious option.

When the European Commission published its draft Withdrawal Agreement in February 2018, it indeed proposed that the SEM be maintained via certain provisions of EU law governing wholesale electricity markets ‘apply[ing] to and in the United Kingdom in respect of Northern Ireland’. A dedicated Annex would list the applicable EU acts, but at this stage the Annex remained blank. A second draft indicated that the UK government agreed on the policy objective but that drafting changes and/or clarifications were still required. When negotiations concluded in November 2018, a slightly adjusted text providing for the application of EU law ‘to and in the United Kingdom in respect of Northern Ireland’ had been agreed, as had the list of EU acts to be applied. Seven acts were listed, and they would be applied if this ‘backstop’ version of the Protocol came into force. Although the text failed to secure approval from MPs and was subsequently ‘renegotiated’ by the new UK government of Boris Johnson, the Protocol’s provisions for maintaining the SEM were left untouched. They entered into force on 1 January 2021 following the end of the eleven-month ‘transition period’ that followed the UK’s withdrawal from the EU on 31 January 2020.

The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland and the SEM

Article 9 of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland sets out provisions to ensure the continued functioning of the SEM following the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. It does so through the continued application in the UK ‘in respect of Northern Ireland’ of seven EU acts concerning the regulation of energy and electricity markets ’insofar as’ they apply to the ‘generation, transmission, distribution, and supply of electricity, trading in wholesale electricity or cross-border exchanges in electricity’. Provisions in these acts that are not necessary for the operation of the SEM do not apply to Northern Ireland.

The seven EU acts applicable under the Protocol, as agreed in 2019, are:

-

- Directive 2009/72/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 2003/54/EC [Electricity Directive]

- Regulation (EC) No 714/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 on conditions for access to the network for cross-border exchanges in electricity and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1228/2003 [Electricity Regulation]

- Regulation (EC) No 713/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 establishing an Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators [ACER Regulation]

- Directive 2005/89/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 January 2006 concerning measures to safeguard security of electricity supply and infrastructure investment [Security of Supply Directive]

- Regulation (EU) No 1227/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on wholesale energy market integrity and transparency (5) [REMIT Regulation]

- Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 on industrial emissions (integrated pollution prevention and control) [Industrial Emissions Directive]

- Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 2003 establishing a system for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Union and amending Council Directive 96/61/EC [Emissions Trading System Directive]

Significant for the operation of the SEM are not only these seven EU acts, but also EU state aid rules as set out in Annex 5 to the Protocol. According to Article 10 Protocol these apply to state aid that could distort competition in the SEM as well as to state aid related to the supply of energy in general into Northern Ireland. Of particular relevance are two Commission Guidelines that apply under Article 10 Protocol regarding:

Moreover, any replacements of or amendments to EU acts applicable under Article 9 Protocol (SEM) or Article 10 Protocol (State Aid) automatically apply as part of the Protocol’s provisions on dynamic regulatory alignment between Northern Ireland and the EU. As with EU acts applicable in Northern Ireland concerning the free movement of goods, the application of EU acts under Article 9 Protocol and Article 10 Protocol is subject to the jurisdiction of the EU Court of Justice.

These arrangements are also, however, subject to ‘democratic consent’ under Article 18 Protocol. Consequently, from late 2024, members of the Northern Ireland Assembly will vote on whether they wish Articles 5-10 Protocol to continue to apply. If there is a majority in favour, then MLAs will be offered the opportunity to vote again after another four years. If the majority is ‘cross-community’, the next opportunity for a democratic consent vote will be after eight years.

Important to note here is that MLAs will not vote on the continued application of each of the Articles 5-10 individually. Consideration of the continued application of the provisions in Article 9 on the SEM will be part of a single vote on Articles 5-10 as a package. If, therefore, MLAs fail to provide democratic consent owing to objections regarding arrangements for the free movement of goods (e.g., owing to concerns over formalities, checks, and controls on goods coming to Northern Ireland from Great Britain) then the default position is that all of Articles 5-10 will cease to apply after two years. During those two years, however, the UK and the EU will consider ‘necessary measures’ to be taken. This could include agreement for the Protocol’s arrangements to support the continued operation of the SEM to continue to apply.

Dynamic Regulatory Alignment and the SEM

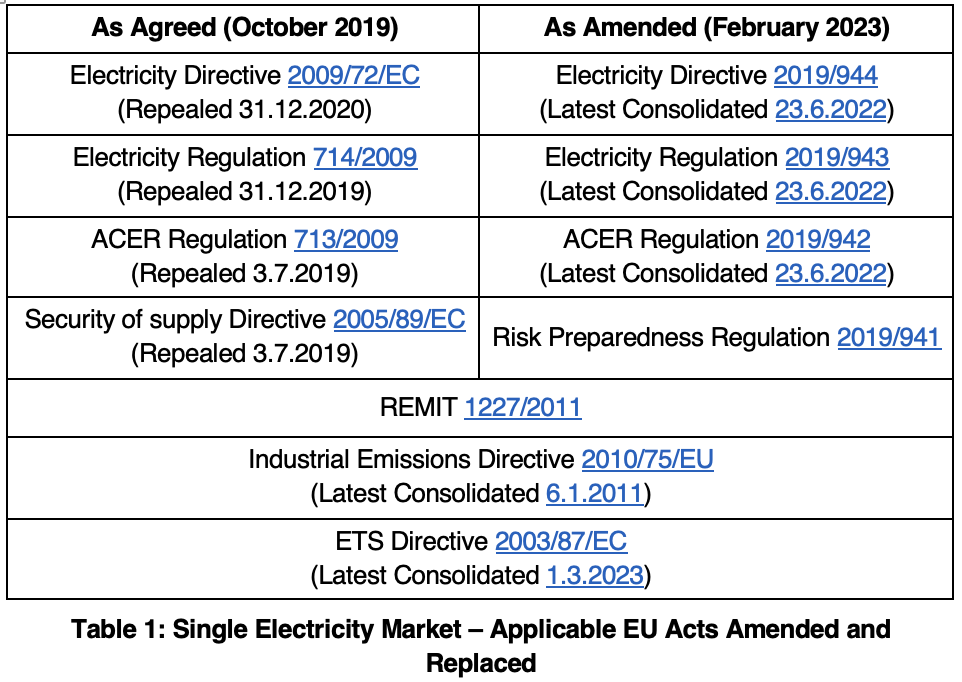

The seven EU acts in the scope of Article 9 and Annex 4 of the Protocol when the text was finalised between the UK and EU in October 2019 have changed as a result of ordinary EU legislative processes.

Two categories of change have taken place: (1) the repeal and replacement of EU regulations/directives with new EU regulations/directives and (2) revision and amendment of still applicable EU regulations/directives via EU implementing legislation. Under Article 13 Protocol, any such ‘amendments or replacements’ apply in Northern Ireland automatically.

Implementing changes adopted by the EU in June 2019, while the UK was still a Member State, four of the seven acts originally listed in Article 9 Protocol were repealed and replaced between July 2019 and December 2020 (see Table 1). Older versions of the Electricity Directive, the Electricity Regulation, and the Agency for Cooperation of Energy Regulators’ (ACER) Regulation were replaced with new, updated versions.

These were part of the ‘Clean energy for all Europeans package’ which sought to decarbonise the EU’s energy system in line with the objectives of the European Green Deal. The electricity market design elements included here sought to increase flexibility in the system to facilitate a greater share of variable and decentralised renewables on the system such as through new rules on demand response and citizen energy communities.

As part of the ordinary processes of EU law making ‘implementing’ or ‘delegated’ legislation is often used to make detailed or technical provisions for the application of a particular EU instrument (regulation/directive/decision) – according to powers granted under it. This process is equivalent to the use of secondary legislation in the UK system to make provisions for the implementation of a specific primary act of domestic law.

In the EU context, when a considerable number of changes have been made to a particular EU instrument, via implementing legislation, a ‘consolidated text’ version of the original instrument is often published in which all relevant updates are reflected.

Although not a direct measure, the development of consolidated text versions of specific instruments does provide an indication of the extent of change taking place, primarily via implementing legislation, under its terms.

As indicated in Table 1 since the end of the UK Transition Period on 1 January 2021, consolidated text versions of four of the seven EU instruments that apply under Article 9 have been published meaning that they have been changed.

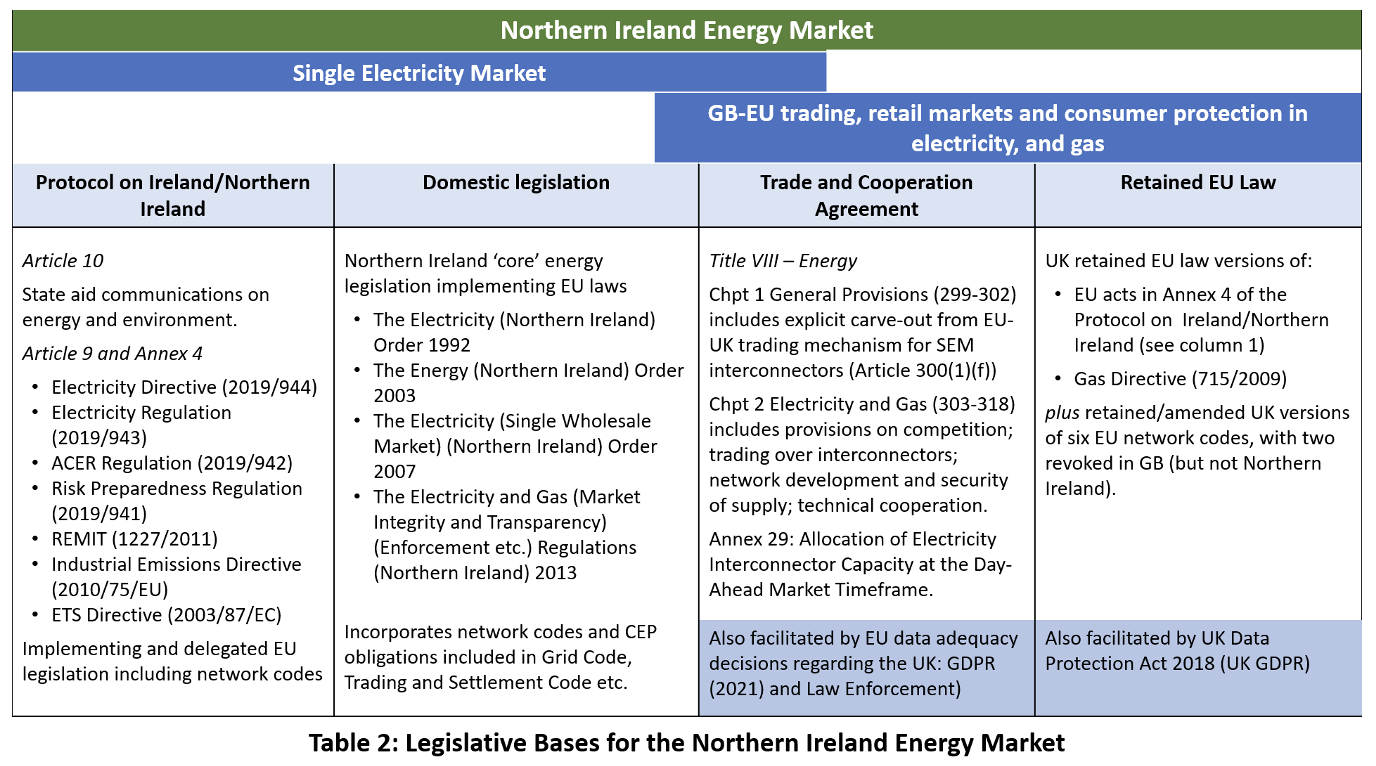

The Protocol, Domestic Legislation and the Trade and Cooperation Agreement

The legislation adopted at the European level is given effect at the domestic level through a range of legislative and regulatory means (see Table 2). In addition to the direct effect of EU Regulations in Northern Ireland, the legislation annexed to the Protocol is primarily given effect in Northern Ireland through the Electricity (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 and the Energy (Northern Ireland) Order 2003 via regulations that took effect under the European Communities Act 1972. Requirements under EU legislation are also made binding on market participants through their licences, granted by the Utility Regulator or SEM-C as well as through the network codes, the rules of the market.

Application of EU law and therefore participation in the EU trading mechanisms only operates North-South to enable the continuation of the SEM. Trading between the SEM and Great Britain takes place under bilateral arrangements which are less efficient than had the UK as a whole remained in the IEM.[4] Arrangements established under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement to make this trade more efficient have not yet been implemented by the UK and EU. In February 2023 a Council Decision (EU) 2023/274 on the position to be taken by the EU under the TCA regarding EU-UK electricity trading arrangements was published – this suggests that an agreement between the two parties is forthcoming.

The Windsor Framework and the SEM

Although the Windsor Framework does make some changes to the Protocol and its implementation these have no material impact on its provisions for maintaining the SEM. The same seven EU acts listed in Annex 4 continue to apply and the ‘Stormont Brake’ allowing MLAs, under certain conditions, to block the application of amendments and replacements to EU acts applicable under the Protocol does not extend to the acts. However, a second ‘Stormont Brake’ provided for in domestic UK legislation that will normally require MLAs to vote in favour of any new EU acts being added to the Protocol does apply may have implications for Article 9 Protocol and the SEM in future, although it is unclear whether and when any relevant new EU Acts will be introduced.

The effects of the Windsor Framework are more likely to be more indirect. Changes to customs and VAT regulations could reduce the cost of materials for the construction, operation, and maintenance of energy infrastructure; a commitment to utilise the institutional framework for the Protocol could lead to substantive dialogue on reviewing the implementation of the SEM provisions, for example on the non-application of provisions ‘relating to retail markets and consumer protection’. There is also the question of how improved relations between the UK and the EU could lead to improved UK-EU energy cooperation, e.g. in electricity trading between Great Britain and the SEM where inefficiencies exist; indications that an agreement on EU-UK electricity trading under the TCA may be imminent are notable in this regard.

The Post-Brexit Operation of the SEM: some issues and challenges

As the UK and EU move toward meeting their climate goals, electricity trading will continue to be affected by an evolving political and regulatory landscape. In 2021 the EU launched its Fit for 55 package with measures to meet a 55% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030. This included changes to its Emissions Trading Scheme and a new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, both of which have implications for the post-Brexit operation of the SEM. There is then the question of what the UK government’s Retained EU Law bill could mean for the SEM.[5]

Under the Protocol, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) continues to apply to the UK in respect of Northern Ireland as it relates to the generation of electricity. The EU ETS therefore applies to Northern Ireland’s three fossil electricity generators in Northern Ireland while the UK ETS applies for all other relevant sectors. It requires companies in some sectors to bid for a finite number of permits to cover their carbon emissions. The UK and EU are committed under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement to ‘give serious consideration to linking their respective carbon pricing systems’ (Article 392). This has been supported by industry in the UK, Ireland and across the EU. The issue was discussed in the relevant TCA committee in October 2022, but without any agreement being reached on whether and how to link the systems. Linking of the EU and UK carbon pricing systems in future could improve their efficiency and reduce complexity in Northern Ireland.

When initially introduced in September 2022, the UK Government’s Retained EU Law (REUL) Bill would have seen most EU law that was copied onto the UK statute book after Brexit, expire (or ‘sunset’) at the end of 2023, unless actively retained. Eight months later the Business Secretary, Kemi Badenoch, announced a change of approach implemented via amendment to the draft legislation. Instead of ‘sunsetting’ most REUL by default, the amended Bill proposed to sunset a specific list of 586 REUL instruments at the end of 2023 while at the same time empowering UK Ministers to reform or revoke those not listed in new Schedule 1 of the REUL Bill. While this change in approach was welcome insomuch as, if enacted, it would result in considerably less legal uncertainty than the previous iteration of the ‘sunset’ clause promised, it still raises some questions for Northern Ireland and the operation of the SEM, at least potentially. This is because, of the 586 REUL instruments listed for revoking, 42 relate to the implementation of three EU acts which, under Protocol Article 9, still apply in Northern Ireland to the extent necessary for the continued operation of the SEM. While this overlap between instruments of GB-retained EU law listed for revoking and Protocol-applicable EU law does not necessarily create difficulties, it is likely that it will have at least some intra-UK divergence implications albeit limited in this instance to Northern Ireland retaining relevant laws as required for the operation of the SEM.

Conclusion

Although a lesser discussed aspect of the ‘unique circumstances’ of Northern Ireland in the context of Brexit, the example of the Single Electricity Market underlines their often-practical nature. Ensuring that the SEM would continue to operate in the aftermath of UK withdrawal from the EU was a comparatively uncontroversial priority during the withdrawal negotiations, no doubt partly due to early cross-party support for addressing the issue.

May 2023

Download a copy of this Explainer here.