Safeguarding the Union

What is new in the DUP deal and what does it mean for the Windsor Framework?

Katy Hayward and David Phinnemore

February 2024

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

The UK Government has published the ‘Safeguarding the Union’ Command Paper to present a package of measures to secure the DUP’s return to power-sharing in Northern Ireland. The Command Paper works within the scope of what was in the UK Government’s gift to give, in accordance with UK-EU treaty obligations. But this is not to say it does not contain anything of substance. This Explainer considers what is new in this deal and the ways in which it goes beyond the Windsor Framework.

Introduction

Key to the return of the Northern Ireland Assembly and a functioning Northern Ireland Executive has been the United Kingdom Government’s Safeguarding the Union ‘deal’ with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). Set out in a Command Paper and accompanying legislation, the package is designed to assuage DUP concerns regarding the effects of the post-Brexit arrangements for Northern Ireland (NI) agreed by the United Kingdom (UK) and the European Union (EU). Set out in the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland (2020), those arrangements exist:

to address the unique circumstances on the island of Ireland, to maintain the necessary conditions for continued North-South cooperation, to avoid a hard border and to protect the 1998 Agreement in all its dimensions. (Article 1(3))

To achieve those objectives now that Northern Ireland is outside the EU and Ireland still inside, the arrangements, among other things, place Northern Ireland in a unique relationship with the EU. Under the Protocol, more than 300 EU laws (primarily on the production and movement of goods) continue to apply in Northern Ireland. Any amendments or replacements to those EU acts automatically apply in Northern Ireland, as they would for a member state. If disputes arise over the interpretation of the EU law that applies in Northern Ireland, the ultimate place for settling these is the Court of Justice of the EU.

The majority of voters in Northern Ireland are broadly content with this unique set of arrangements as a compromise that enables the region to avoid some of the most disruptive effects of Brexit and to keep some benefits associated with free access to the EU internal market for goods. But there has been strong opposition in Northern Ireland to the Protocol. With the rest of the UK now outside the EU customs union and internal market, the effect of these arrangements – coupled with the effects of the UK’s Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU – is the requirement for formalities, checks and controls on the movement of goods between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. There have also been concerns around the legal underpinning of the arrangements and what it means for Northern Ireland’s status.

In sum, concerns have centred around five main themes:

-

- the principle of differentiated treatment of Northern Ireland within the UK and within the UK-EU relationship;

- the ‘democratic deficit’ inherent in the process of dynamic regulatory alignment;

- the disruptive effects the differentiated arrangements have on Northern Ireland’s position within the internal market of the UK;

- the potentially adverse effect of regulatory divergence between the UK and the EU on Northern Ireland’s position within the UK internal market (i.e. British-made goods no longer eligible for sale in Northern Ireland);

- the consequent suspicion or fear that the Protocol undermines Northern Ireland’s constitutional position within the UK.

Such concerns are reflected in the ‘seven tests’ that the DUP set in 2021 and demanded to be met before it would countenance a return to Stormont following its collapse of devolved government in early 2022.

To address these concerns, the UK and the EU reached agreement on a package of measures contained in the Windsor Framework in February 2023. We have written elsewhere about what that deal means for Northern Ireland. It includes easements and facilitations on the movement of goods across the Irish Sea from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, mainly by differentiating between goods destined to stay in Northern Ireland and those heading on into the EU. It also sees new mechanisms to give a role to the Assembly vis-à-vis the Protocol, including the introduction of a ‘Stormont Brake’ for use on certain amendments or replacements to EU law applicable under the Protocol. This deal resulted in a slight increase in acceptance of, if not necessarily outright support for, the Protocol’s arrangements for Northern Ireland. For the DUP, however, the Windsor Framework did not go far enough in assuaging concerns, and so discussions with the UK Government continued. These eventually culminated in the Safeguarding the Union deal at the end of January 2024 and the subsequent decision of the DUP to return to devolved government in Northern Ireland.

The UK Government’s Safeguarding the Union Command Paper presents a package of measures and commitments to address concerns regarding the implementation and effects of the Protocol/Windsor Framework. This includes three pieces of draft legislation – the Windsor Framework (Constitutional Status of Northern Ireland) Regulations 2024, the Windsor Framework (Internal Market and Unfettered Access) Regulations 2024, and the Windsor Framework (Marking of Retail Goods) Regulations 2024 – together with new or amended implementation guidance, and the promised establishment of new bodies/structures. The Windsor Framework (as the Protocol is now known) remains unaltered by this deal – it could not be changed without further UK-EU negotiation and agreement. However, there is quite a lot that is new about this ‘deal’ that has substance and, potentially, significance for Northern Ireland and its relationship with its closest neighbours. This Explainer focuses on precisely how the deal goes beyond the Windsor Framework and considers what this might mean and what we are yet to find out.

Safeguarding the Union

The Safeguarding the Union Command Paper claims to ‘copper-fasten’ Northern Ireland’s place in the Union. In legislative terms, this relates most directly to two pieces of secondary legislation as part of the Windsor Framework (Constitutional Status of Northern Ireland) Regulations 2024. The first amends Section 38 of the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 – the Act underpinning the legal effect in the UK of the Protocol/Windsor Framework. It does so by asserting that the Windsor Framework is without prejudice to the constitutional status of Northern Ireland, including the power of the UK Parliament to make laws for Northern Ireland. The reference to ‘Northern Ireland’s part in the economy of the UK, including its customs territory and internal market’ is also new. A second amendment to the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 prohibits the Government from ratifying a ‘Northern Ireland-related agreement with the European Union’ that would ‘create a new regulatory border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland’. This is presented as ‘future-proof[ing] the constitutional status of Northern Ireland against any future agreements that create new EU law alignment for Northern Ireland and undermine its place in the UK’s internal market’ (para 6).

New bodies and structures

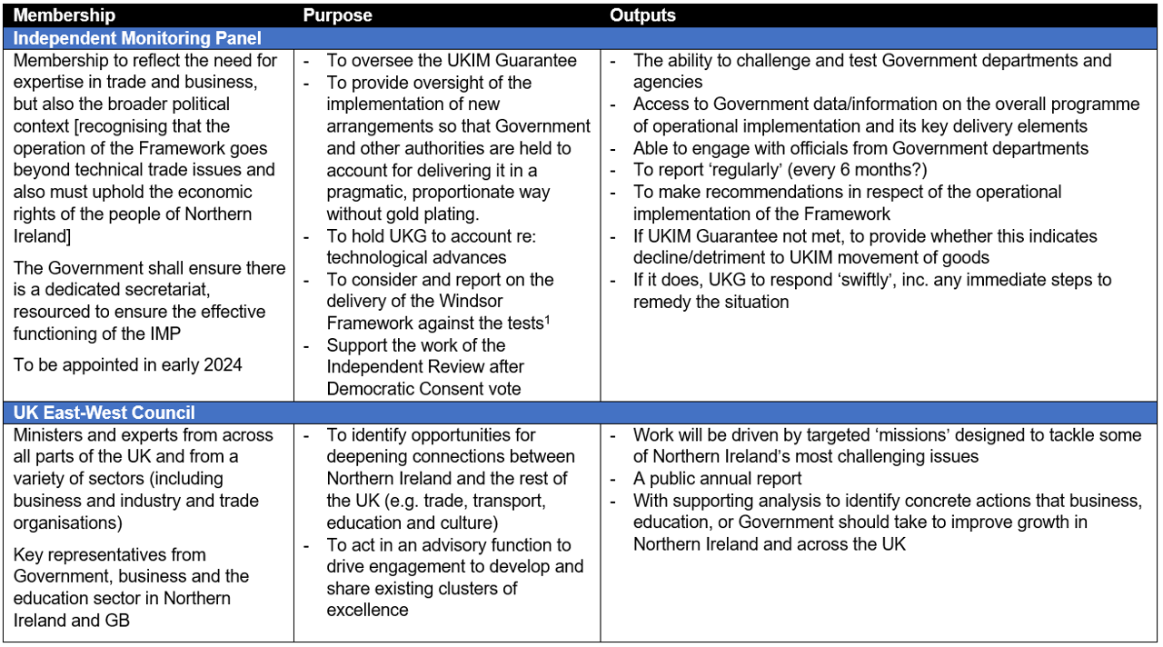

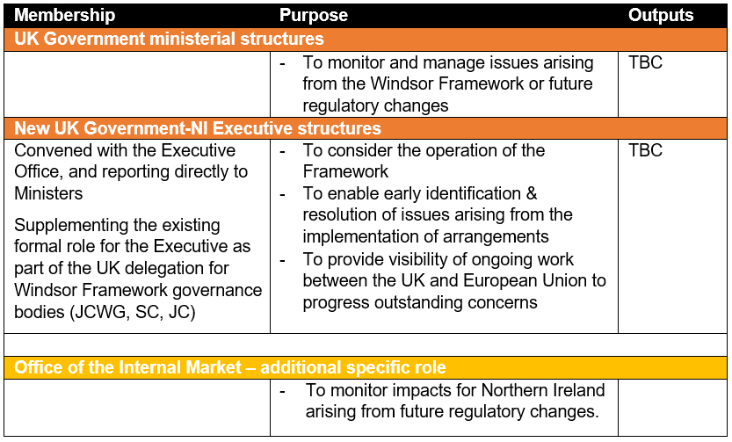

The most substantive elements of Safeguarding the Union package lie in the establishment of new bodies and structures. The new bodies are:

-

- An Independent Monitoring Panel

- A UK East-West Council

- Intertrade UK

- A Horticulture Working Group

- A Veterinary Medicines Working Group

There is much that is unknown about these bodies, not least in terms of the scale of the challenge that they will have to address, the effects of their operation, and their interaction with other bodies. However, Safeguarding the Union does set out their essential purpose and their anticipated outputs as well as their membership (see Table 1, below).

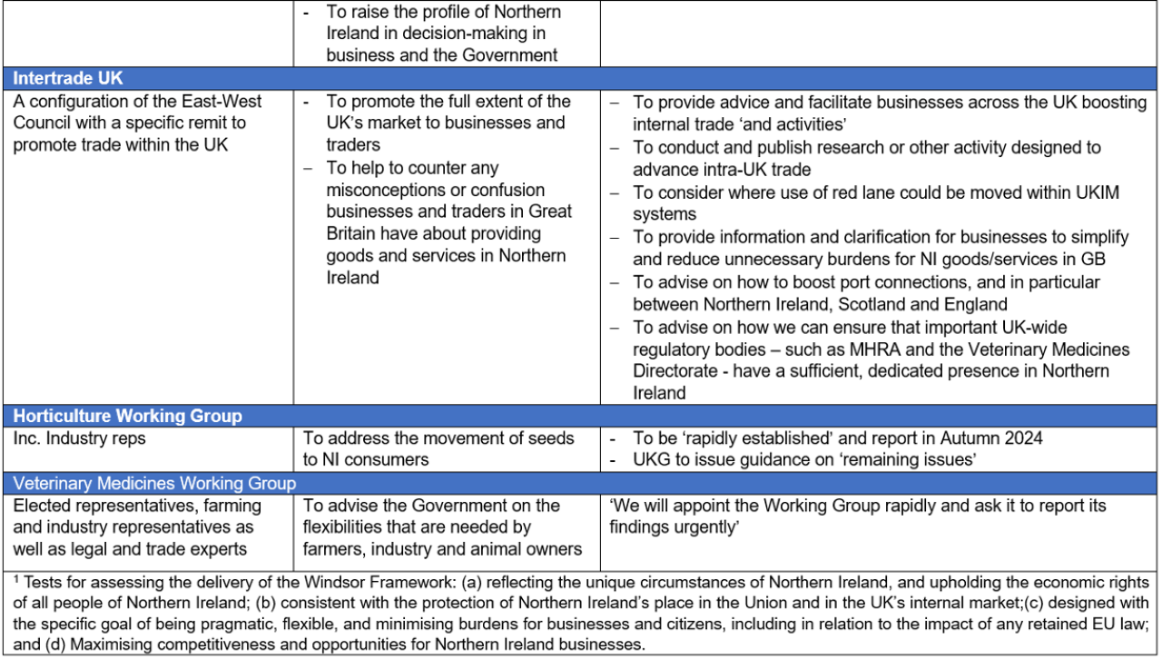

There are also some new structures and roles for government bodies and officials that look set to improve communication and coordination between Whitehall and the NI Civil Service (see Table 2, below). Such measures have been recommended since the Protocol was first unveiled.

Northern Ireland's Place in the UK Internal Market

The Safeguarding the Union Command Paper introduces an Internal Market Assessment which requires that the Regulatory Impact Assessment carried out by public authorities in the UK have to consider whether measures will have ‘an adverse effect on the UK’s internal market’ (para 148). The stated purpose of this is ‘to avoid Whitehall applying unnecessary regulatory burdens on business in any part of the UK’ (para 43t).

There is also a statutory transparency obligation (an amendment to Section 13 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018) which means that a Minister in charge of a Bill is to make a statement if the Bill contains provision which, if enacted, would affect trade between Northern Ireland and other parts of the UK. Notably, even if the Minister cannot claim that it will not negatively impact such trade, the government still may wish to proceed with it. This manages to meld the regulatory divergence/deregulation ambitions of pro-Brexit Conservative MPs with assurances for unionists and NI businesses about their position within the UK internal market. It is not a commitment to align with the same rules as the EU that Northern Ireland follows under the Windsor Framework.

Relatedly, through the Windsor Framework (UK Internal Market and Unfettered Access) Regulations 2024, new statutory guidance is to be issued under section 46 of the UK Internal Market Act 2020 to ‘set out how public authorities should have special regard to Northern Ireland’s place in the UK internal market, to avoid gold-plating and support the free flow of goods between Great Britain and Northern Ireland’ (para 43q).

Safeguarding the Union also includes measures affecting GB-based businesses, and irrespective of whether they are selling goods in Northern Ireland or not. The UK Government’s commitment to extend the range of products ‘for which CE markings will be recognised indefinitely’ (para 144) helps minimise the risk of discrimination in Great Britain against NI goods for which CE markings are required under the Protocol. Such a commitment is likely to be welcomed in GB given that it has been sought by businesses across the UK.

Rather less welcome to GB businesses could be the legislation – the Windsor Framework (Marking of Retail Goods) Regulations 2024 – to ensure that, from 1 October 2024, the ‘Not for EU’ labelling required of GB-produced goods for sale in Northern Ireland under the Windsor Framework is also to apply to all GB-produced goods for sale in the UK. Perhaps in recognition of the difficulties that this may cause some traders, the government has launched a public consultation (ending 15 March 2024) ‘on how to implement these requirements most effectively’. There is draft legislation but it remains only in ‘indicative’ form until the results of the public consultation are considered.

Also subject to public consultation will be the UK’s version of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which (according to the Command Paper) will be implemented within a year of the full roll-out of the EU’s own CBAM. When the UK is notified of the EU’s CBAM proposals, the Command Paper confirms what we know from the Windsor Framework, i.e. that they will only be applied in Northern Ireland under the Protocol if there is a cross-community vote in the Assembly in support (para 153).

Changes relating to movement of goods from GB to Northern Ireland

The Command Paper commits the UK Government to ensure 'no unnecessary checks within the UK internal market’. This is the same as in the Windsor Framework, which provides for decreasing to minimal levels checks on goods that are staying in Northern Ireland. It is acknowledged that, even within the UK Internal Market System (the new name for the ‘green lane’), checks will be ‘conducted by UK authorities and required as part of a risk-based or intelligence-led approach to tackle criminality, abuse of the scheme, smuggling and disease risks’, which would be the grounds for the checks as expected under the Windsor Framework (paras 9, 93, 96).

One new commitment in Safeguarding the Union that does go beyond the Windsor Framework is set out as a ‘UK Internal Market Guarantee’. This is the Government’s commitment ‘that more than 80% of all freight movements from Great Britain to Northern Ireland [will] take place under the UK internal market system, with independent scrutiny’ (para 88). This relates to the fact that the ‘green lane’ is to be renamed as the ‘UK Internal Market System’ – which makes a lot of sense given that there were already two forms of the green lane under the Windsor Framework – the NI Retail Movement Scheme and the UK Internal Market (UKIM) Scheme – and that there were never plans for a physical green ‘lane’ per se.

The UK Government’s claims about the ‘free flow of goods’ overlap considerably with ambitions it has for the development of its Border Target Operating Model (BTOM). One example is the promise of more seamless, simple customs information sharing, e.g. with individual profiles for those using the Trader Support Service (TSS) (for customs declarations) based on commercial data rather than commodity codes (para 101). This ambition is already present in the Windsor Framework. The commitment ‘to harness future technological advances’ so as to further reduce the information needed by the TSS, for which ‘trial work’ is already ‘underway with private sector partners’ is joining the dots between the UK Government’s ‘smart border’ ambitions and smoothing the GB-NI movement of goods – something entirely logical (para 102).

Unfettered access for NI goods to GB

A key feature of Safeguarding the Union is the matching of ambition and symbolism with practical requirements. The difficulty of doing so is evidenced in the statement that there will be no Border Control Post built at Cairnryan. This may be seen as a powerful sign of the promise of unfettered NI access into GB, which is particularly important now that GB borders are becoming harder as checks and controls are rolled out as part of the BTOM. However, the lack of a Border Control Post does raise the question of how to manage Irish/EU goods that enter GB via Northern Ireland. For this, future actions are promised: ‘we will develop an approach to checks and formalities on non-qualifying goods entering GB via Cairnryan’ (para 121). This will be a test for balancing the promise of unfettered access with the need for avoiding an open backdoor into the GB market to non-UK goods.

Safeguarding the Union also includes legislation to tighten the definition of Northern Ireland qualifying goods (i.e. those goods that qualify for unfettered access to the GB market). A revised definition means that only agrifood goods connected to registered NI food and feed operators will qualify for unfettered access to the GB market. This is intended to prevent goods produced in Ireland from using Northern Ireland as a gateway into GB thereby avoiding the hardening GB border controls (e.g. for goods moving Dublin-Holyhead). Further discrimination (as is necessary in border controls) between GB and Irish businesses is to come in the form of ‘ensuring’ that Irish operators using the red lane to access the EU (Ireland) through Northern Ireland ports ‘pay the normal fees and charges that apply elsewhere across the UK and Ireland/the EU’ (para 132). Details on how that will happen in practice are still to be published and rolled out.

Changes relating to the NI Assembly

To address concerns about dynamic regulatory alignment under the Protocol/Windsor Framework, Safeguarding the Union introduces a further – and much-trumpeted – piece of secondary legislation. This is The Windsor Framework (Constitutional Status of Northern Ireland) Regulations 2024 noted above. They amend Section 7A of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 to note that dynamic regulatory alignment is subject to the operation of the Stormont Brake and the Democratic Consent vote in the Assembly – mechanisms that were already provided for under the Windsor Framework and Protocol, respectively. The scope and effect of these mechanisms are not expanded by this legislation. Instead, the publication of operational procedures for the use of the Stormont Brake – including advance notice of proposed EU acts and setting out what information MLAs need to provide the UK Government when wishing to see the Brake activated – are presented as ‘strengthening’ its operation.

Regarding the Democratic Consent vote, The Windsor Framework (Constitutional Status of Northern Ireland) Regulations 2024 place an Independent Review of the Windsor Framework on a statutory footing. A commitment to such a review in the instance of a Democratic Consent vote on Articles 5-10 being passed with a simple majority (the first vote being due in December 2024) was made in 2019 when the Protocol was agreed. Now, through an amendment to the Northern Ireland Act 1998, the UK Government has a statutory duty to initiate the review within a month of a vote and report within six months; previously the review had to be concluded within two years of a vote. With Safeguarding the Union, the UK Government also now has a statutory duty to ensure the report of the independent review is fully considered. The scope of the independent review is also expanded such that it ‘may include consideration of any effect of the Windsor Framework in the withdrawal agreement on… the constitutional status of Northern Ireland, and… the operation of the single market in goods and services between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom’ (para 164). The review is also to provide recommendations on the steps the UK Government could make to ensure the UKIM Guarantee will be permanently delivered. Any issues or recommendations raised by the report are to be raised in the EU-UK Joint Committee that oversees the implementation of the Windsor Framework.

Still to come

One complex issue that remained unresolved by the Windsor Framework is the continued supply of ‘necessary veterinary medicines’ in Northern Ireland beyond the end of the current grace period in 2025. A Working Group on the topic is to be established and to report back in fairly rapid order. In the medium term, the UK Government commits to ‘pursuing an agreement with the EU on a long-term basis (if necessary, by a guarantee of flexibilities that would be deployed by the Government)’ (para 43r). This sounds rather like a Veterinary Agreement with the EU, which could potentially be sought by the next Government. In the meantime, the Government promises, on the back of a new veterinary medicine working group (para 141), to set out plans in the spring of 2024 to introduce legislation that would avoid new regulatory divergence between GB and Northern Ireland on veterinary medicines (para 43r).

Also still to come is the repeal of Section 10(1)(b) of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 which requires that in exercising its functions UK Government ministers give ‘due regard’ to the 2017 Joint Report of EU and UK negotiators that paved the way for the Protocol. The report includes reference to UK alignment with EU law to 'support… the all-island economy’. Although no such commitment exists in Protocol/Windsor Framework, Section 10(1)(b) arguably confers on the UK Government a ‘legal duty’ to do so – something this Government deems ‘unacceptable’. In addition, a commitment to ‘a full and complete repeal of all statutory duties relating to the 'all-island economy' is described as a ‘statutory protection that underlines and further ringfences Northern Ireland’s place in the UK’s internal market.’ The change will also be reflected in statutory guidance issued under the UK Internal Market Act 2020.

Safeguarding the Union?

Given the concerns surrounding the substance and the real and anticipated effects of the Protocol/Windsor Framework identified above, how far does Safeguarding the Union go in addressing them? Politically, the UK Government’s commitments and draft legislation have been sufficient for the DUP to agree to the return of the Assembly and the establishment of a new Executive. In terms of the substance and operation of the Protocol/Windsor Framework, the essential elements remain broadly untouched, although adjustments have been made to some aspects of implementation. Fundamentally, the UK Government’s recognition that it can make Northern Ireland’s unique position either easier or more difficult is a large step forward. The new bodies – if they are resourced and given a clear remit – could help keep the Government on track with its commitments, or at least ensure the position of Northern Ireland remains under active consideration in the legislative process in Westminster. In addition, the UK Government has made a set of practical commitments and measures (e.g. new ministerial structures) regarding implementation of the Protocol/Windsor Framework that could well help Northern Ireland manage challenges – and realise opportunities – in collaboration with the rest of the UK.

Safeguarding the Union is a welcome next step in the process of minimizing the disruptive effects of Brexit on Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland’s place within the post-Brexit UK-EU relationship. It demonstrates a willingness on the part of the UK Government to address sensitively and pragmatically, if not fully, a set of concerns about the Protocol/Windsor Framework and to do so while respecting rather than threatening to breach its international treaty obligations. Moreover, with the DUP returning to the Assembly on the basis of the Safeguarding the Union ‘deal’, a moment has been reached where the five largest political parties in Northern Ireland are now at least implicitly accepting of the Windsor Framework arrangements. Whether commitments are honoured, and whether concerns about the Protocol/Windsor Framework are steadily assuaged in practice, will help determine the stability and longevity of this Assembly.

Table 1. New bodies to be established (according to the Command Paper)

Table 2. New structures/roles to be established (according to the Command Paper)

Download a copy of this Explainer here.